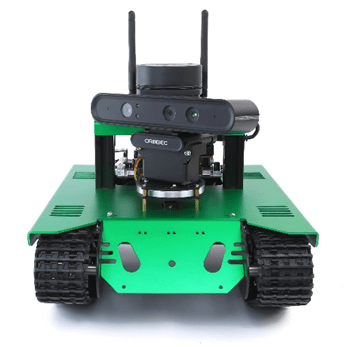

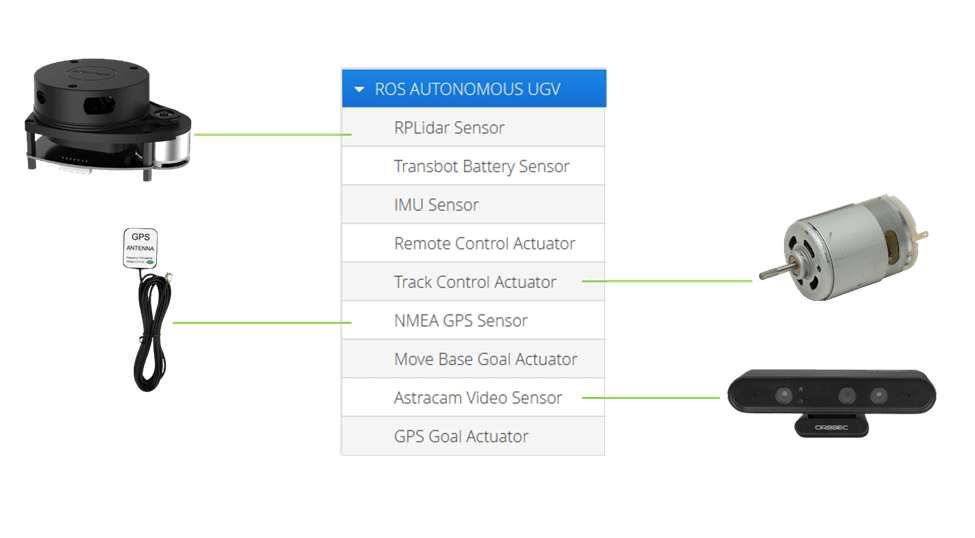

In the past, we wrote a brief article on OpenSensorHub (OSH) integration with robotics platforms where we used an inexpensive STEM platform (“Yahboom G1 AI vision smart tank robot kit with WiFi video camera for Raspberry Pi 4B”), stripped the software and wrote a completely OSH centric web-accessible services solution for monitoring and tasking the robot. The entire software stack was hosted on the on-board Raspberry Pi. However, we were lacking the location-enabled and geographically aware aspects to this solution simply because we did not equip it with its own GPS unit. We also explored running OSH on Nvidia Jetson cards and making use of the GPUs to improve the processing necessary to augment sensor observations with SensorML process chains making use of artificial intelligence, machine learning, and computer vision. The ideal solution would be to combine the capabilities of the Robot Operating System (ROS) with OSH to create truly location-enabled, geographically aware, web-accessible robotics platform powered by Nvidia Jetson single board computer (SBC). To this end we acquired another, albeit more expensive but not prohibitively so, STEM robotics platform – The Yahboom Transbot ROS package. This system includes a SLAMTEC RP-Lidar A1 (2-dimensional), an Orbbec Astra Pro (RGB and Depth Camera), a wireless PS-2 like controller, and an Nvidia Jetson Nano with a hardware interface board. This package includes prebuilt ROS-1 packages on Ubuntu 18.02 Linux and an optional downloadable smart phone app. To complete the solution, we added a compatible GPS module that could be connected via USB to the SBC.

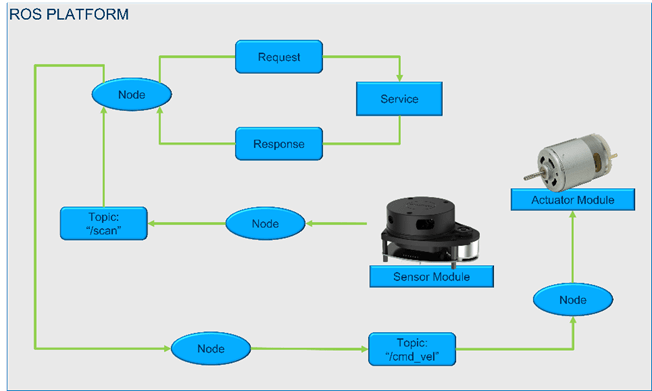

The Robot Operating System (ROS) is an open-source, meta-operating system providing services typically provided by an operating system such as hardware abstraction, device control, inter-process communication (PubSub – publish and subscribe), and package management. ROS can also operate as a distributed system in which the various processes, known as nodes, can be executed on one or more computing platforms. The ROS ecosystem provides implementation for commonly used functionality, including modules for many commercially available sensors and actuators. Additionally, ROS provides packages for autonomous Simultaneous Localization and Mapping (SLAM) navigation whereby a robot can estimate its pose and position within an operating environment while also mapping the environment itself. On a ROS platform each sensor, actuator, process (node, service) is itself a system that can be deployed independent of other elements in the ROS environment. Through the PubSub and Services interfaces the systems become interconnected and together can be used to create hierarchy of systems. Any ROS platform is represented as a computational graph and the entire ROS Computation Graph is in essence a representation of a System-of-Systems.

As ultimately any robotics platform is a system-of-systems, this led us to model the robotics platform as a Connected System (OGC API – Connected Systems – Overview) through configuration within OSH. To do this we established a simple hierarchy where each subsystem (sensor, process, actuators) is modeled as an OSH module. This is important to harmonizing data and treating Observations and Measurements holistically, e.g., like observations from different sensors converted to same units-of-measure (UOM). In addition, it allows us to logically group observation data streams within OSH modules given that systems and subsystems can potentially have many data streams and treating them individually can lead to challenges in client applications. Finally, control streams may be added as part of module or exist as independent and separate modules.

In order to achieve this integration with minimal impact to the robotics platform we opted to run OSH as a remote participant in the robot’s ROS ecosystem. Remember that ROS is a distributed meta-operating system so not all ROS nodes need be present on the target platform. To achieve our objective, we made use of rosjava (github.com) to build a library of classes that allow OSH modules to act as publishers, subscribers, services, or action client nodes. Therefore, any module within OSH can easily be tooled to become a node in the ROS computational graph allowing for both data streams and control streams to and from OSH and a remote robotics platform. By adding a ROS based GPS module to the robotics platform and implementing a sensor module as a subsystem of the Connected System representing the platform in OSH, we can achieve making any ROS based robot a location-enabled, geographically aware, web service available robotics solution. A high-level view of the architecture can be seen in high-level architecture below.

One of the advantages of deploying OSH outside of the robotics platform is that a single OSH instance can in fact communicate with 1 or more ROS platforms to either compose a distributed robotic system or potentially interface with a number of independent ROS platforms. This is accomplished by allowing each OSH module to be configured to participate in a given ROS ecosystem. So, for example, if there are multiple sensors which are not collocated on a single physical platform each with its own ROS instance one can conceive of a single connected system configuration where some OSH modules participate with one ROS instance while other OSH modules participate in another. To an end user or client application there would be no distinction and the entire setup would be considered part of a single connected system. That is to say that a single OSH instance could be used to monitor and task a truly distributed single robotics solution or could be used to orchestrate and plan the actions of a swarm or collection of robotics platforms by collecting observations, performing analysis through SensorML process chains (which can include AI/ML/CV processes) and tasking in a form of tipping and cueing.

Nice.

Do we have a place to keep these docs and make them accessible to outsiders or guest?

Thanks. Mike

>

LikeLike

Nice job! Opens the door to easier development of collaborative fleet operations of all kinds of vehicles. Are these changes available now in https://github.com/opensensorhub, or when will it become available?

LikeLike

They are now available, can be found here https://github.com/opensensorhub/osh-addons/tree/v2/sensors/robotics/ros

LikeLike